Once upon a time

Back in the 1980s, AJ Hackett – a young Auckland builder with a love of thrill-inducing sports – discovered a ritual by Pentecost Islanders by which men throw themselves off 35 metre-high wooden towers, with their ankles attached to vines.

The centuries-old ritual is believed to ensure a good yam harvest on the island in Vanuatu.

AJ Hackett Bungy has been stretching minds since 1986 – starting out with a couple of Kiwi blokes in pursuit of the ultimate adrenalin buzz.

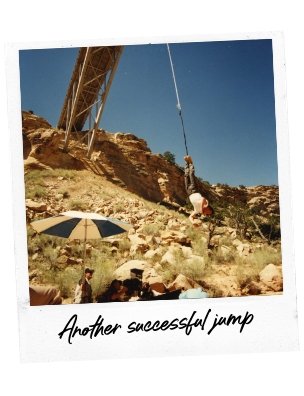

Early Jumps

This daring activity appealed to AJ but he didn’t think much more of it till he met fellow Aucklander Chris Sigglekow in the early 1980s. Chris, a video editor, had seen 1970s video footage of a British group calling themselves the Oxford University Dangerous Sports Club, with young men undertaking a modern version of the Vanuatu jump. But instead of wooden towers, the British men jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

Chris had been inspired by the group’s exploits and had already attempted making a bungy cord with a parachute harness and jumping off the Pelorus Bridge in Marlborough, New Zealand. But the jump didn’t go as planned so Chris shelved the idea till he met AJ.

The pair decided if they could make the activity consistently safe, then they would pursue it further.

“We decided, ok, let’s suss out first of all if we can make this thing predictable. If we can’t make it predictable then we stop – because I like a challenge but I don’t like pain. I don’t want to kill myself but I like to have some fun” AJ says.

THEY APPROACHED THE DEPARTMENT OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH, WHERE THEY DISCOVERED A MATHEMATICAL FORMULA FOR THE BUNGY CORD RUBBER.

So in 1986, armed with their bungy cord, AJ and Chris headed to the Greenhithe Bridge in Auckland to test it out. They threw a test weight – a punching bag full of lead and rocks – over the side, and it worked. It was then their turn to take the plunge.

The following weekend AJ, Chris and friends Henry van Asch and Martin Jones drove to Hamilton to jump off a bridge 10 metres higher. With everyone getting the same buzz, it was decided they’d jump off the 44m-high Auckland Harbour Bridge the next weekend. They did this, and several other 80m-high bridges in the North Island, without getting noticed by the authorities for several months.

“What we discovered was that if you took a single strand of the rubber and stretched it to 6.7-times its length, it would snap. But at four-times its length, it was only using 15 per cent of its breaking strain,” AJ explains.

“All we had to know was the height of the bridge that we were jumping from, divide it by four, less a couple of metres for the length of the person and the harness webbing attachment to the bungy, and that would be the length of the cord.”

“It was Chris’ turn to jump first. So we took out the old parachute harness from the wardrobe from five years before and he jumped. He just missed the water, bounced up, just missed the under-side of the bridge, and it was perfect,” AJ recalls.

“He undid the chute and swam out, still had a smile on his face, and now it was my turn. So I jumped off, got the same rush; so we both did another one each and we were so stoked and excited about the whole thing. We’d realised that these calculations and theory all actually worked after all that, so that’s where the story began.”

IT WASN’T TILL AJ, HENRY AND MARTIN WERE DUE TO FLY OUT TO EUROPE AS PART OF THE NZ SPEED SKIING TEAM IN 1986 THAT THEY GOT CAUGHT IN THE ACT.

The friends had decided to jump off the Auckland Harbour Bridge a second time before they boarded their flight to France. AJ had devised an ankle-tie system and he wanted to try it out, instead of using the original parachute harness. It meant that he’d be jumping head-first instead of feet-first.

Henry and Martin jumped successfully, but as AJ and Chris were about to jump, the police boat Deodar arrived beneath them, with police ordering the pair not to jump. Realising they’d been caught, they jumped anyway. Police, keen to deter others from doing the same thing, contacted Television New Zealand for a story on warning people not to jump off bridges. The story handed AJ and his bungy idea publicity on a plate.

Eiffel Tower

AJ arrived in France keen to do some speed skiing but also determined to take bungy to another level. He discovered the Pont de la Caille – a 147m-high bridge – where he successfully jumped off using the ankle-tie technique.

He also approached French scientists to find out how the bungy cord rubber would handle in freezing cold situations.

Realising it could be done, he managed to convince management at Tignes ski resort to let him jump head-first off a cable car. He braved minus-20degC temperatures and successfully jumped 91m into deep snow.

It was to be the first of many “extreme” jumps for AJ – but nothing like his famous Eiffel Tower jump in Paris, June 26, 1987.

“I had this dream of jumping from a cable car into the snow and skiing off. It was kind of this romantic vision,” AJ says.

“When we’d first arrived in Paris we drove past the Eiffel Tower and I thought wow, that’s a really beautiful structure, I’d love to jump off this building,” he recalls.

“So I measured the tower, figured it out how to jump from it, sorted out how the security worked, where the cameras were and all that sort of thing. One evening in Paris a big team of us went up to the tower. It was just closing, the girls were carrying bungy under their dresses, and in backpacks we had ropes and gear and camera crews and sleeping bags.

“Security all disappeared and so we settled in for the night and early the next morning the alarm went off too late so it was a rush job trying to get it rigged up, and finally we were ready to go.”

“Anyway I jumped, the jump went perfectly and I was really happy to pull it off. And then the gendarmerie [French police] came from everywhere. They couldn’t figure out what was going on at all. And the rest is history, really.”

AJ’s stunt attracted worldwide media attention – the best form of publicity he could possibly ask for, and it put bungy jumping at the forefront of peoples’ minds.

Commercial

AJ returned to New Zealand with the intention to develop bungy for use in movies and commercials – because he thought it would be too difficult to establish a commercial operation for public bungy jumping.

While continuing to refine the bungy systems, he grabbed more headlines when he jumped off the Auckland Stock Exchange building in 1988. It was to be the world’s first jump from a building.

That same year, he was ready to offer the thrill to the public. He set up the world’s first commercial bungy site in Ohakune in March 1988.

“I discovered on the very first jump that I did personally that we were on to something incredibly special,” AJ explains.

“And I thought, surely I’m not unique, everyone must feel this – or most people must feel this. So quickly we jumped a number of friends, both men and women, to see whether they actually got the same reaction. I wanted it to be for everybody.”

AJ set his sights on the historic Kawarau Bridge in Queenstown as his ideal location for bungy jumping – and so on November 12, 1988, the first year-round commercial operation was launched. On that day, 28 people paid $75 each to jump off the 43m-high bridge with a bungy cord attached to their ankles.

The Kawarau Bridge operation wasn’t without its challenges – AJ and Henry van Asch, who became business partners, needed to raise money and get permission to restore the old bridge and build improvements, including the visitors’ platform, walkways and reception building.

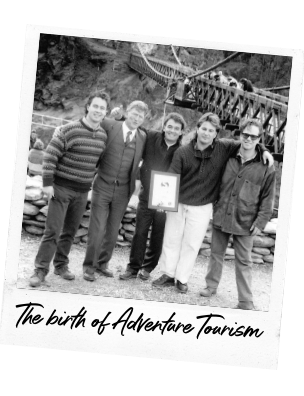

THE LAUNCH OF THE KAWARAU BUNGY SITE HAS BEEN HAILED AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF ADVENTURE TOURISM IN NEW ZEALAND AND NOW ATTRACTS MORE THAN 500,000 PEOPLE EACH YEAR.

Determined to make bungy jumping a completely safe activity, AJ and Henry developed a Bungy Code of Practice in 1989, which provided the framework for the New Zealand/Australian Bungy Jump Standard.

After that, his quest to discover bigger, more exciting jumping places began.

He opened commercial bungy operations in Normandie, France, on August 9, 1990, and Cairns, Australia, on August 11, 1990. The Cairns Bungy site was the first purpose-built bungy tower in the world.

Later that year, AJ jumped 390m from a helicopter in Normandie – a world-first and a stunt that got him into the Guinness Book of World Records. The world’s first commercial helicopter bungy operation began in New Zealand in 1993 and exceeded 3000 jumps. Today, the world’s only heli-bungy exists at AJ Hackett’s Germany operation.

Bungy sites in Las Vegas, USA, and Kuta Beach, Bali, followed in 1994 and 1995, respectively.

In 1997, Queenstown’s second bungy site, the Ledge, opened in response to public demand. That same year, AJ and Henry van Asch decided to go their separate ways and operate independently. Henry now owns and operates all New Zealand bungy sites and AJ owns and operates the international enterprise. The split was amicable and both parties continue to work together in areas of safety, customer satisfaction and joint marketing initiatives.

In 1998, AJ developed a new cable system to stabilise the jump – enabling accurate jumps to be executed from high structures. This process allowed him to break the world record for a building jump – 190m fall from Auckland’s Sky Tower. The jump was witnessed by 10,000 people in the streets below and nearly 1 million people tuned in to watch it live on television.

AJ Hackett Bungy celebrated its millionth customer in July 1999 and shortly after, AJ further-expanded operations at his Normandie site, as well as opening at Condesa Beach, Acapulco, Mexico.

That same year Queenstown’s third bungy site, the Nevis Highwire Bungy, also opened to the public. The Nevis includes the world’s only purpose-built bungy gondola, positioned 134 metres above the Nevis River, and is the highest bungy in Australasia. It also includes the world’s biggest swing with a 300-metre arc.

IN 2000, THE GIANT JUNGLE SWING - THE WORLD’S BIGGEST JUNGLE SWING – OPENED AT THE CAIRNS SITE.

AJ Hackett International has formed global distribution partnerships with several other inventors of high-adrenaline activities, including Skyjump – a controlled descent machine specifically designed for tall towers.

In 2006, the world’s highest bungy from a tower opened in Macau, China. The Macau Tower measures 233m above the ground. In 2008, the 61m-high Normandie Viaduct Swing opened to the public.

AJ Hackett Bungy celebrated a huge milestone in November 2013 – marking 25 years of commercial bungy where it all began, in Queenstown.

AJ’s passion and commitment to growing bungy internationally continues. In May 2014 he opened new sites in Sochi, Russia, and Sentosa, Singapore.

“We’re continuing to expand all over the planet and also broadening our base of activities – all sorts of vertigo and personal-challenge related – where people have to push their own buttons to take themselves out of their comfort zones.”

Skypark

2020 shaped as a year unlike any other. On top of managing a global pandemic, we celebrated our 30th birthday in both Cairns and Normandie, opened up a brand new site in Moscow Russia and launched our new brand identity - Skypark by AJ Hackett.

Skypark celebrates everything that AJ Hackett is famous for; creating positively life changing experiences through our range of gravity defying activities, whilst creating a destination of all inclusive fun activities you will want to keep coming back for. Check out each individual site to experience the many worlds of Skypark by AJ Hackett.